We present a conservative extension of a Bayesian account of confirmation that can deal with the problem of old evidence and new theories. (.) Thus I submit that the case against the realist’s thesis that success is indicative of truth is marginally strengthened. In this paper I argue that this will be difficult for the ionised helium success, and is almost certainly impossible for the fine-structure success. Many scientific realists would like to be able to explain these successes in terms of the truth or approximate truth of the assumptions which fuelled the relevant derivations. Two successes of old quantum theory are particularly notable: Bohr’s prediction of the spectral lines of ionised helium, and Sommerfeld’s prediction of the fine-structure of the hydrogen spectral lines. For these reasons, these arguments are fallacious, and thus do not pose a serious challenge to scientific realism. I also show that the historical episodes that Stanford adduces in support of his New Induction are indeterminate between a pessimistic and (.) an optimistic interpretation. The so-called Old Induction, like Vickers's, and New Induction, like Stanford's, are both guilty of confirmation bias-specifically, of cherry-picking evidence that allegedly challenges scientific realism while ignoring evidence to the contrary. Kyle Stanford and Peter Vickers, are fallacious.

In this article, I argue that arguments from the history of science against scientific realism, like the arguments advanced by P. In particular, I will not try to defend it (.) against the sort of criticisms Bettis says an Arminian might raise.

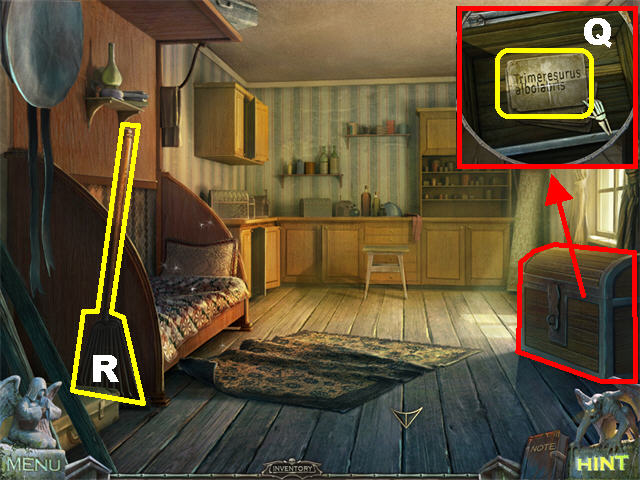

Torrent redemption cemetery la maledizione del corvo crack full#

I will not attempt a full defence of universalism here, however. I would like to argue that either some of Bettis's criticisms are confused, or else that he is not using ‘love’ in anything like its ordinary sense. In his article ‘A Critique of the Doctrine of Universal Salvation’, J.īettis criticises the argument that all men will be saved because ‘God's love is both absolutely good and absolutely sovereign’. For reasons related to those that arise in Scotus's failed attempt to refute the principle, the principle also entails that properties cannot be universals. I argue that Scotus's various counterexamples to the principle can be rebutted. / Richard Cross Scotus's belief that any created substance can depend on the divine essence and/or divine persons as a subject requires him to abandon the plausible Aristotelian principle that there is no merely relational change.

I conclude with some reflections on various senses of being metaphysically special and how they pertain to primary substances and supposits. Next, I turn to a parallel issue about supposits, which Boethius seems in effect to identify with primary substances, and how theological cases-the doctrines of the Trinity, (.) the Incarnation, and of the human soul's separate survival between death and resurrection-call into question how and to what extent supposits are metaphysically special. I then consider how medieval reflection on Aristotelian change led medieval Aristotelians to analyses of primary substances that called into question how and whether they are metaphysically special. Marilyn McCord Adams In this paper I begin with Aristotle's Categories and with his apparent forwarding of primary substances as metaphysically special because somehow fundamental. Soldiers, who enlist in order to advance justice by just means, deserve the chance to fight and perhaps to die with the fully formed moral assurance that their cause is right. The paper claims that soldiers have relevant and important ideas about the justice of the (.) cause.

Contesting this claim, the present paper reasons that without the moral confidence of the soldiers who serve, no conflict can be justified. Thomas Aquinas, that a sovereign might identify a just cause and declare war without reference to the nation’s soldiers or citizens, continues to inform thinking about just war. The jus ad bellum doctrine of legitimate authority, conceived by St.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)